Wieteke Theeuwen LL.M.1

The first lesson I learned when I started working on cyber was - or seemed - rather simple. International law applies to cyberspace. In that regard, I would like to quote one very important phrase from the 2013 report of the UN Group of Governmental Experts (UN GGE) on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security:

"International law and in particular the United Nations Charter, is applicable and is essential to maintaining peace and stability and promoting an open, secure, peaceful and accessible ICT environment."

Thanks to the 2013 and the 2015 UN GGE reports, there is increasing recognition that international applies to cyber. So, many would agree with me that international law applies to cyberspace. When we start to apply the law and ask ourselves how international law applies to cyberspace the question is a more interesting one.

Part of my work has a focus on “the Hague Process”, an initiative by the Netherlands to further the debate on how international law applies in cyber space and to increase the level of agreement. For this purpose the Netherlands facilitated a number of consultation meetings between governmental legal advisors and the drafters of the Tallinn Manual.

The Tallinn Manual 2.0

The Manual is a well-used item in our library at the legal department. I carry it with me to meetings all the time. The book provides a good overview of the various legal questions that arise with respect to cyber and offers different views on the application of international law but it is not the law. It is not an official document, and the Netherlands does not necessarily agree with everything in it. In fact, in many cases the manual describes more than one possible interpretation of a particular rule. I consider the Tallinn Manual to be a very useful tool that we can use in our daily work. Whenever I am asked to advise on an issue relating to cyber and international law, I use the standard work for the specific field of law together with the Tallinn Manual, which provides helpful information on how this law may be applied in the cyber context. But the manual does not do all the thinking for me. To the contrary, the Tallinn manual 2.0 makes it very clear that there are a number of questions that still need a lot of thinking and debating before we can even dream of providing an answer to them. Which makes meetings like these so much more interesting.

Attribution

Attribution has been the object of fierce debate. More specifically, attribution for the purposes of State responsibility - or legal attribution. Generally, depending on the context, the term attribution has different meanings when we talk about cyber.

My colleagues and I find it helpful to make a distinction between the following meanings of the word:

1) Technical attribution: the outcome of a factual and technical investigation both in terms of who the likely perpetrator is and the degree of certainty with which this can be established;

2) Political attribution: the decision whether or not to publicly and politically attribute a particular attack to a particular actor, without necessarily attaching legal consequences to this attribution; and

3) Legal attribution: the decision to attribute certain conduct to a particular State with a view to invoking the responsibility of that State for an internationally wrongful act.

Focusing on legal attribution, I am referring to the situation in which a State attributes a cyber operation to another State for the purpose of invoking State responsibility. The first State may then wish to enter into some form of judicial or diplomatic dispute settlement to take countermeasures or, in case the cyber operation is considered to amount to an armed attack, exercise its inherent right of self-defense.

Why is attribution important? When your car is stolen, or your house is covered in graffiti overnight, you want to take action. But against whom? That is why we go to the police when things like this happen: so that they can find out who did it and who deserves punishment. The same goes in international law: this body of law provides rules with regard to how States should behave towards each other, but it can only be applied when it is clear who violated the rules. When cyberattacks, or any attack for that matter, are launched, international law sets the parameters within which States can respond. The law on State responsibility, the example I will use, has a lot to say about when a State can be held responsible for the conduct of a proxy. It also allows taking measures that would normally be in breach of international law in order to address a prior breach by another State. But in order to do this, it is crucial to establish which other State committed the wrong in the first place.

So why is it important to be able to attribute a cyber operation to another State? When a cyber operation is directed against a State, or significantly impacts the society of that State, that State will want to take action. Certain action is only possible when it is clear which other State should be at the receptive end of such action. So, once a State has identified the actor behind the cyber operation and has established that this actor is in fact another State (either directly or by proxy), the targeted State has a number of options under international law.

Examples of responses are retorsive measures, unfriendly but not unlawful, such as the decision to declare a number of diplomats persona non grata. The taking of retorsions is permitted under international law, but may carry political consequences.

A State may also consider taking countermeasures, such as responding to a hack that constitutes an internationally wrongful act by hacking back. These are different from retorsive measures. Whereas retorsive measures can be taken at any time – again, this is according to international law, without taking into account possible political considerations – countermeasures are subject to strict requirements. This is reflected in the ILC Draft Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts. One of the most important criteria of these Articles is that countermeasures may only be taken against a State that is responsible for an internationally wrongful act, in order to induce that State to comply with its obligations. One requirement for such responsibility is that the conduct, the allegedly unlawful cyber operation, is attributable to that State. There are other requirements, but these will not be discussed.

Therefore, for a State to be able to consider all its response options, including countermeasures, the first question it will need to ask is: who did it? In legal terms: can the cyber operation be attributed to a State under international law? That is when legal attribution becomes important.

What is an internationally wrongful act?

Before discussing what the Tallinn Manual 2.0 says about internationally wrongful acts in the cyber context, I would like to first discuss the Draft Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts.

What amounts to a breach of international law by a State depends on the actual content of that State’s international obligations, and this varies from one State to the next. A State can only be held accountable with regard to obligations it has subscribed to, either by treaty or through customary law. The underlying concepts of State responsibility, however, are general in character.

Article 1 of the draft Articles states that every internationally wrongful act of a State entails the international responsibility of that State. But what does this act need to consist of?

Article 2

There is an internationally wrongful act of a State when conduct consisting of an action or omission:

(a) Is attributable to the State under international law; and

(b) Constitutes a breach of an international obligation of the State.

I will discuss attribution, not the entire characterization of conduct as internationally wrongful. The purpose of attribution is to establish that the act considered as internationally wrongful emanates from a certain State for the purposes of responsibility. That a certain conduct is attributable to the State says nothing, as such, about the legality or otherwise of that conduct.

So when is a cyber operation attributable to a State? Let me turn to the conditions under which conduct is attributed to the State as a subject of international law for the purposes of determining its responsibility. What it essentially does is distinguish the State-sector from the non-State sector for the purpose of responsibility. Basically, conduct by State organs is always attributable to a State whereas conduct of private individuals is not, unless a sufficient connection between these individuals and the State can be established.

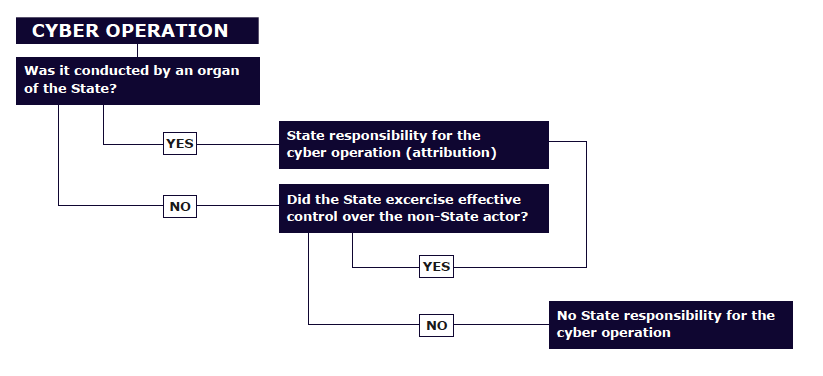

This graph explains the questions that need to be answered before a cyber operation can be attributed to a State.

The first question we need to ask in order to determine whether a cyber operation is attributable to a State is “Was the cyber operation conducted by an organ of the State?” If the answer is yes, the cyber operation is attributable to the State.

Rule 15 of the Tallinn Manual 2.0 states:

Cyber operations conducted by organs of a State, or by persons or entities empowered by domestic law to exercise elements of governmental authority, are attributable to the State.

The Tallinn Manual states that the clearest case of attribution is when State organs, such as the military or intelligence agencies, commit the wrongful acts. This includes for instance cyber activities of US Cyber Command, the Netherlands Defence Cyber Command, the French Network and Information Security Agency (ANSSI), and so forth. An organ of the State includes any person or entity which has that status in accordance with the internal law of the State, quite a broad concept according to the Tallinn Manual.

With cyber operations it is not always immediately clear whether the operation originated from an organ of the State. The use of proxies is very common in the cyber context. If it is not clear whether an individual or group are considered organs of the State, we need to determine whether their conduct can nonetheless invoke the responsibility of the State.

Proxies are individuals, groups or organisations carrying out cyber operations for States. This is the reality we are facing relatively often in the cyber context. We may be able to find which individual, group or organisation carried out the cyber operation, but can we link this to a State, and if so, how? Can the conduct of hacktivists be attributed to a State? What if the State told them to carry out a certain cyber operation? This brings me to the effective control test.

Effective control

When does a non – State actor operate under effective control of a State? As a general principle, the conduct of non-State actors such as private persons or entities is not attributable to the State under international law. The effective control test contains certain requirements that – if fulfilled – will allow to regard the conduct of the non-State actor as that of the State. This is the only way in which the conduct of proxies can be attributed to a State.

The conduct of a person or group of persons shall be considered an act of a State under international law if the person or group of persons is in fact acting on the instructions of, or under the direction or control of, that State in carrying out the cyber operation. The starting point is, however, that States are not responsible for the conduct of private individuals. This means that the threshold to establish effective control is high. It is not sufficient for example if a State has supported – financially or with supplies – the activities of the non-State actor.

Standard of proof

As regards the standard or burden of proof, international law does not dictate any minimum degree of proof regarding the decision to attribute a particular cyber operation politically to a particular State. Likewise, there is not a particular threshold of certainty for responses not amounting to countermeasures or the use of force.

However, if a State attributes a cyber operation to another State and takes countermeasures, or in case it exercises its inherent right of self-defence when the cyber operation is considered to amount to an armed attack, it may at some point have to provide justification for this attribution and meet a particular burden of proof. There is no internationally accepted legal standard in this respect. It will depend on the particular forum in which attribution takes place. The standard of proof required may differ depending on whether a claim is presented before a particular international court or tribunal, or whether it is part of diplomatic negotiations or consultations. The ILC Draft Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts do not include information on the standard of proof. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has employed various formulations for the standard of proof. The Netherlands interprets these formulations as meaning that the standard may be different depending on the severity of the conduct and of the response considered.

Various cases show that the Court similarly pays regard to the specifics of the case when determining the level of proof required.

It would seem that the particular degree of proof required is closely connected to the severity of the cyber operation and of the response to such cyber operation: the more severe, the higher the standard. In some cases one may need to have absolute or near absolute certainty. For example, in the Bosnia Genocide the ICJ took the view that the Court had to be fully convinced that allegations of genocide and other acts had been clearly established. This concerned genocide. It makes perfect sense that a high degree of certainty, employed in different cases, would not have been sufficient.

How does attribution of cyber operations work in practice?

In May 2017 WannaCry ransomware targeted computers by encrypting data and demanding ransom payments in Bitcoin. The WannaCry Cyberattack affected a number of healthcare organisations in the United Kingdom (UK), including hospitals in London and Nottingham. So how did the UK respond?

19 December 2017 - Foreign Office Minister for Cyber, Lord Ahmad:

“The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre assesses it is highly likely that North Korean actors known as the Lazarus Group were behind the WannaCry ransomware campaign – one of the most significant to hit the UK in terms of scale and disruption.

[…]

We condemn these actions and commit ourselves to working with all responsible States to combat destructive criminal use of cyber space. The indiscriminate use of the WannaCry ransomware demonstrates North Korean actors using their cyber programme to circumvent sanctions”.

So did the UK attribute the cyber operation to a State? To me, this question is difficult to answer. The UK referred to North Korean actors, not the State.

How did the United States (US) respond?

19 December 2017 - Tom Bossert, security adviser to the President:

“Cybersecurity isn’t easy, but simple principles still apply. Accountability is one, cooperation another. They are the cornerstones of security and resilience in any society. In furtherance of both, and after careful investigation, the U.S. today publicly attributes the massive “WannaCry” cyberattack to North Korea.

[…]

The United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Japan have seen our analysis, and they join us in denouncing North Korea for WannaCry.”

Not only did the US refer to the State North Korea in its attribution, it also mentioned that the UK shares that analysis. A number of States issued statements on that same day, the 19th of December, varying from the very strong statement by the US to a statement on the importance of the application of international law by others.

None of the statements were followed by countermeasures. Why not? And why were they taking so many months after the attack took place? Was the information the States had at their disposal not considered sufficient enough to satisfy the standard of proof? Maybe the public statements were never intended to lead to the taking of countermeasures in the first place.

Conclusion

Attributing a cyber operation to a State for the purpose of State responsibility is subject to a number of requirements, especially when the operation is carried out by proxies. It is a very delicate process. But the process is not more delicate than attribution outside the cyber context. The example I mentioned concerning WannaCry shows that a new phenomenon has emerged: publicly attributing a cyber operation. This type of attribution might not fulfill the requirements for legal attribution, but does it need to?

However, if a State decides to take countermeasures, legal attribution is very important. I mentioned at the beginning that with the Tallinn Manual we have been provided with a very useful tool, but a number of questions still need a lot of thinking and debating. Let me conclude with some of these questions. Is the effective control test workable in the cyber context or do we need to develop further criteria? Should the challenges related to technical attribution lead to adjusting the standard of proof for legal attribution in the cyber domain? Do we agree that the various formulations of the standard of proof employed by the ICJ in State responsibility cases must be interpreted as meaning that the standard may be different depending on the severity of the conduct and the response considered?